The term “community” indicates a similarity, a likeness, and a sense of being one. When a group is identified as having common ways of thinking, behaving, and communicating, it can be considered a discourse community. More specifically, James Porter defines it as “individuals bound by a common interest who communicate through approved channels and whose discourse is regulated”. By defining a discourse community in this way, he incorporates the elements of regulation and approval into the notion of unity and likeness. Being part of a discourse community means that there are certain approved ways of doing things and of sharing ideas. To be part of this community means understanding what these ways are, and for the most part, abiding by them in order to gain membership.

What are some of these discourse communities to which we belong? One’s family—immediate and extended—are examples of discourse communities. We write email, text, tweet, post entries, write family newsletters, hold family meetings, or plan reunions and gatherings via spreadsheets. There are certain ways we behave that meet expectations within the family, and defying those norms results in problematic situations for the group as well as the individual. We also share a common vocabulary with our families which make possible for shared stories and recollections. Other discourse communities? Parent-teacher organizations, church groups, volunteer organizations, professional organizations, craft groups, tennis leagues—among a few. Members of these groups communicate with each other and with other groups in order to further the purpose of the community. To do so effectively, what is expressed and how members express these ideas, whether spoken or written—must be aligned with the conventions existing in the group.

For several years, I helped put together the school newsletter for my K-4 school community, and as part of that editorial board, I remained mindful of the group’s standards—what is acceptable to include and what is not, how best to present news, when to distribute the newsletter, how to request for interviews, etc. To stray from these conventions would mean a loss of readership and support or worse yet, social isolation from members of the community.

A discourse community works to regulate what and how something is written or spoken. At the same time, changes can also be introduced to these existing standards so long as the member is deemed “qualified “to do so (Porter). When we finally shifted from paper newsletters to online only, I was grateful to other qualified members who supported my suggestion. At that point, the change was seen as valid, and as such was accepted by the discourse community. Yet, if I had presented that same suggestion maybe a few years prior—when I might not have been seen as “properly socialized” to the discourse community (Porter), then the change may have been seen as unacceptable and invalid. The newsletter would not have gone paperless.

We all belong to one or more discourse communities (this class, English 503, being one of those!). In this academic discourse community, we write and go about our work in prescribed ways in order to further our purpose of learning from and interacting with each other. A discourse community puts forth certain demands as it regulates content and process of written communication. Because of this, certain tensions and conflicts may arise, and a community, in spite of the commonality that exists, will allow for this as well. We face conflicting demands of the work expected from us as graduate students versus our personal timetables, ways of thinking, and styles of writing. To proceed and uphold the norms and ethos of the discourse community, there is a need to negotiate these conflicting demands. Because we want to be successful ENG 503 students—the identity we are constructing as we are “socialized” into the discipline—we work to fulfill the demands of the course alongside other endeavors that fill our time. We commit and participate actively to “produce competent, useful discourse within that community” (Porter).

I am part of another academic discourse community—that of the community college where I teach and coach writing. As part of that community, I produce syllabi, assignment sheets, quizzes, reflection prompts, session reports, portfolio assessments, rubrics and feedback, as well as email for both students and colleagues. This academic discourse community, along with most others, maintains a clear set of standards and benchmarks to regulate membership. Faculty and high achieving students are considered qualified members of the group, socialized into its language practices and norms of communication. Being such, faculty and proficient students feel they belong to the college community. This strengthens their identity as successful members, and in turn, motivates them to participate even more actively.

Predictably, successful students complete their programs and transfer to 4-year institutions or begin their careers. However, not everyone experiences this socialization process. Large numbers of students feel they do not belong to the college discourse community. They end up alienated and isolated, and eventually give up membership all together. These students do not return and fail to complete their programs. Students who arrive at my developmental classes run a higher risk of experiencing this alienation. Because of a complex set of factors, it is difficult for them to adapt readily to the communication and language practices of the college. While difficult, it is not impossible however. As an instructor and a socialized member of this discourse community, how do I respond to this situation? How do I balance the demand of the community to regulate discourse, with the responsibility to socialize its newest members? Which role do I prioritize? There are no easy answers to this.

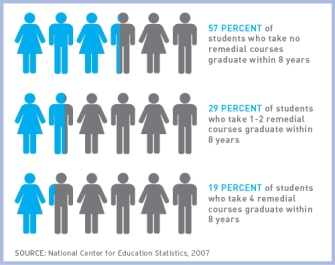

College completion rates as correlated with remedial coursework load

Students who find it a challenge to incorporate the standards of discourse in college often enter the community confused about or unaware of the “rules” governing it. Prior years of schooling may not have equipped them with the resources to be aware, let alone understand and apply these unspoken rules of successfully navigating work in college. As an instructor and a writing coach, I have to opportunity to engage in conversations that slowly make what is unknown, known—ways of writing and explaining that are considered valid and acceptable in a college discourse community and how it might apply to their ways of writing at the moment. These conversations aim to help the students connect their current language practices—perhaps accepted in other fora like Facebook or family conversations—to expected language practices in the college community. It does not invalidate what they know or what they do; instead, it works to get them situated within the discourse community they hope to join. It seeks to balance the task of regulating with the work of inclusion. While at times frustrating and usually challenging, the work remains worthwhile. Discourse communities thrive when membership is broad and inclusive—membership from both teachers and students. New ideas and ways of doing things breathe life into the community, and in doing so, keep thinking fresh.

References

Collins, M. L. (2013). Strengthening State Policies to Advance Postsecondary Success and Careers. Jobs for the Future. Retrieved from http://www.jff.org/initiatives/postsecondary-state-policy

Porter, J. (1986). Intertextuality and the discourse community. Retrieved from https://bblearn.nau.edu/bbcswebdav

Hi, Tessa? TESSAQUINO 🙂

Great post. You caught my interest with your opening line: “The term “community” indicates a similarity, a likeness, and a sense of being one.”You methodically and neatly organized your thoughts around the fabric of discourse that brings together a community. I found your example of how timing of communication, and what not to include as well as what to include, are equally important in communication within a social circle. You started with family and branched out into various other kinds, evening giving each attention and examples of kinds of discourse and their relevance. Great balance on content.

I was quite interested in how this discourse can make or break a university student’s success. It is such a vital transition in life, and for some, it is the time they leave the nest, and have a much larger group or undefined place in the world. I felt you empathized with students in flux and brought the reader in alignment with that empathy.

If I could offer any suggestions, I would say the ending could have had a paragraph to reinforce the ideas presented, and/or launch the reader off into though with a bit more gusto. Overall, enjoyable read. Thanks for sharing.

Rhea

LikeLike

Hi Rhea,

Yes, Tessa is absolutely fine 🙂

Thanks for your comments. I appreciate how you’ve pointed out the balance that you found earlier in the post. Also how you’ve felt the need for more support towards the end. Let me take a closer look at that and see where I might reinforce those ideas.

Thanks for stopping by to share your thoughts!

Best,

Tessa

LikeLike

Like Rhea I enjoyed the progression of your blog from the familial to collegiate. I could not help relating the transition you mention to my own context of grade school to high school. Likewise some students are not prepared and have much more difficulty with their acclimation. I think my only critique would be that I would have liked to see some suggestion to solve the issue you raise. While your program is clearly one, you even admit that sometimes it is not enough. What types of interventions might help more acclimate and not be lost? I know that in my context we have meetings one level to another for alignment which hopefully makes the transition smoother… is that possible going up to college?

LikeLike

Hi Leigh,

Good to share the comment space with you again! Glad you found a point of connection in the post—that of transitioning in your years of school. That is such a real part of most, if not all, students’ experiences, and it can be quite jarring until roles and expectations are clarified. There is so much work that goes in school in addition to the explicit “work of school”—books, papers, classes, etc—and preparation and readiness is so unique to an individual.

I will certainly look at trying to include a few suggestions to elaborate on the points I make while trying to stay withing the scope of my discussion.

Thanks for stopping by again to comment!

Best,

Tessa

LikeLike

You offer a strong introduction and clear definition of discourse community, and the sources are both well integrated and explained. Your title helps to establish the point that becomes even clearer in your second paragraph – the notion of how we abide by certain rules and conventions to keep membership within a particular discourse community and how they serve to “further the purpose of the community.” I love how you use the K-4 newsletter to even better illustrate your ideas; this example reminds your audience how deviations from the community rules for discourse can cost you your membership, or in this case, readership and connection to the other members of the community. Better still, how the notion of going online was also a suggestion that had to abide by the validation and acceptance of everyone involved.

I know as a teacher myself, though at the secondary level, how crucial it is to ensure that the discourse we involve in “strengthens their identity as successful members, and in turn, motivates them to participate even more actively.” Every day I and my colleagues are working to improve how we accomplish this and get them engaged, participating, and actively involved in all aspects of their learning and success. When a student feels estranged from that community, the costs are tragic in so many ways – social isolation, reduced engagement, refusals to participate, resignation to the possibility of learning or success, and possibly even dropping out. With the kinds of number we see today in students who don’t finish high school, it is more important than ever to emphasize this point you illuminate so well. I know that even at the college level working to ensure students identify well enough with the discourse community is of utmost importance, as the percentage of students who graduate reflect as much on that institution as it does on mine.

You ask powerful and necessary questions on behalf of every educator, particularly, “how do I respond to this situation?” In my current coursework with Dr. Gruber (ENG 519), we have discussed at great lengths the importance of student engagement, collaboration/classroom communities, real-world applications for learning, and developing connections between course content/skills and their personal lives. These are fundamental goals of all of my curriculum designs, and ones that I believe work to support and answer that very question you posed.

Furthermore, teaching the concept of voice and academic language expectations is a challenge for my students as well. It is so important to have the conversations you described: connecting their current language practices to those expected of them in an educational setting.

I wonder if these issues might begin to be addressed more thoroughly at earlier levels with the implementation of national standards? It is my hope that as they progress I begin to see more students who are not surprised when we have these conversations about formal tone and voice.

LikeLike

Hi Brandi,

Thanks for your thoughts. Your discussion digs into some very significant elements in our experiences as teachers. You write: “When a student feels estranged from that community, the costs are tragic in so many ways – social isolation, reduced engagement, refusals to participate, resignation to the possibility of learning or success, and possibly even dropping out”.

Isn’t that true across a number of situations in school—whether secondary, post-secondary, middle, or elementary. Student engagement is essential if any meaningful learning is going to happen. And you aptly point out how the low graduation rates are disturbing. Unfortunately, it is messy business to delve into why it is happening. But, like you, I feel those questions need to be asked, and if we, those right in the classroom don’t do so, who will?

Thanks for stopping by and extending our discussion! Great points to keep reflecting on.

Best,

Tessa

LikeLike

Tessa,

Launching from James Porter’s definition of a discourse community in your introduction carried the idea that he “incorporates the elements of regulation and approval into the notion of unity and likeness” all the way through your post. Value was given to familial discourse as well as other common communities, then carried into the discourse at the academy. Those are effective moves that lead into your specific challenges of teaching, coaching and communicating to developmental students how to become a member of the academic discourse community. By giving value to the communities of which students are already a part, it is easier to help them to bridge the similarities and characteristics of familiar communities by focusing on how they regulate, approve, align conventions and language, and socialize the members in like manner. Well done!

Teresa

LikeLike

Hi Teresa,

Terrific to have you back for another “visit”! Thanks for tracing the “moves” I mapped out throughout my post. I knew what I wrote and why I wrote them, but it is always (and that’s not being hyperbolic when I say always!) so helpful to be able to see one’s work through another reader’s eyes.

As I read through your comment, I get to understand my own thought process better as well. Thanks for that. Just like sitting with a coach at the writing center…except virtually!

Thanks for your time!

Best,

Tessa

LikeLike

Maria,

First of all, great post, but I have come to expect that any time I read something of yours…so no pressure. I am so glad you discussed how family and friends are also considered discourse communities. I think people limit its definition way too much.

I honestly think the key aspect of a discourse community is people trying to make a common goal happen and if that does not entail families and friends, then I am clueless. Thank you for your post.

LikeLike

Hi Eric,

Thanks for your comments! You are too kind, but I am glad that you find something to take from the posts we share in class 🙂

Yes, isn’t that funny? The notion of family and friends as discourse communities themselves isn’t something readily considered. I know I didn’t when I was first trying to understand the concept of discourse communities. It is so much easier to think of it only as connected to school or workplace writing. But, then when you think of a group sharing a set of communicative practices–one that defines them as a group–then applying those lenses to family and friends begins to make sense.

Heaven knows my family has some very unique communicative practices, and membership is reinforce by these funny/unique practices!

Thanks for stopping by to comment!

Best,

Tessa

LikeLike